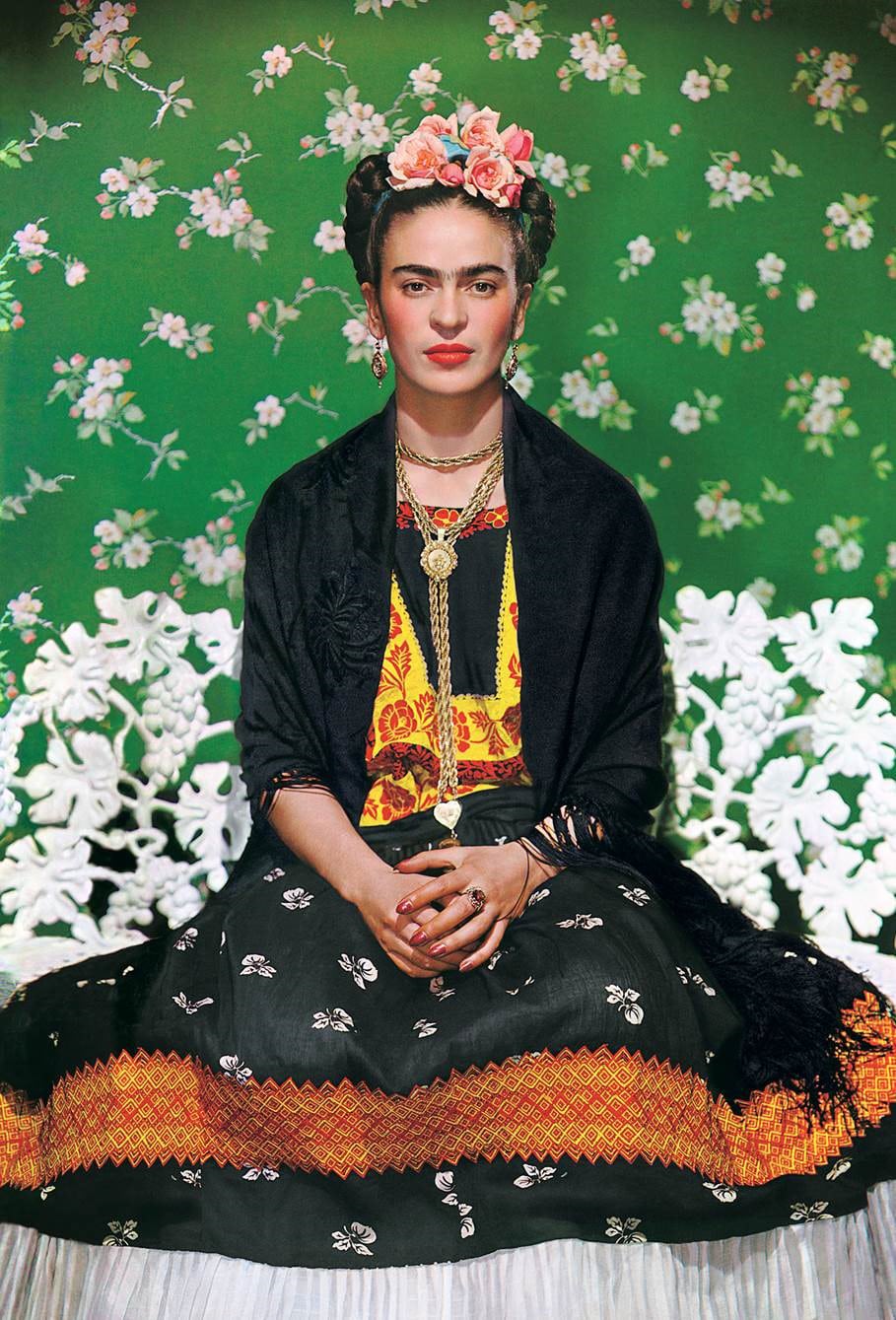

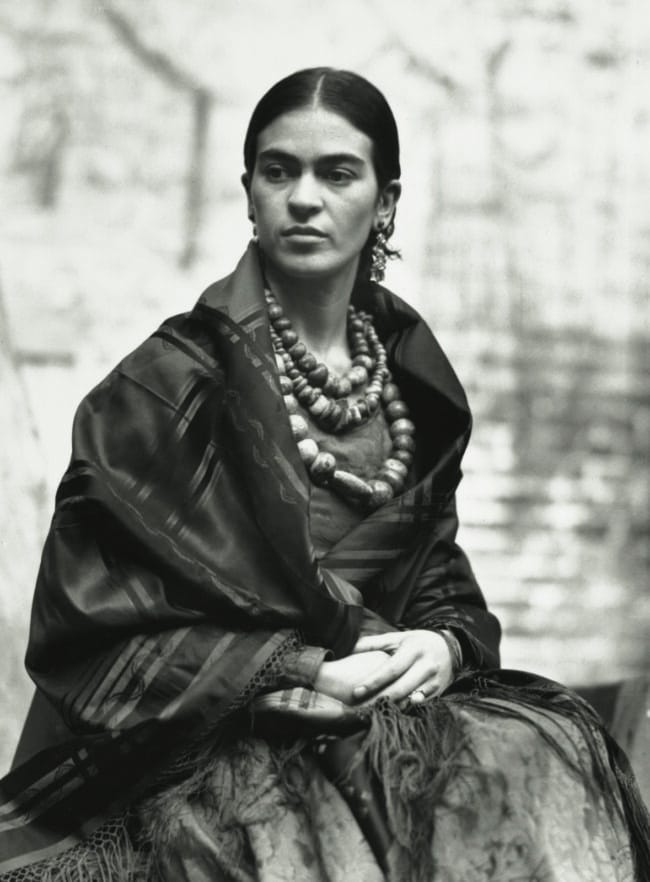

Frida Kahlo (1907-1954) was among the most photographed women of her generation. What photographers found intriguing was her uninhibited humor and charm, overt sensuality and rare beauty and style. She was not shy before the camera. As one admirer noted, “Frida regularly invented and recreated herself with intelligence and verve.”

Mirror, Mirror … Portraits of Frida Kahlo features fifty-seven photographs by twenty-seven photographers. Among the many pleasures in this exhibition is the chance to see something of the “real” Frida Kahlo, that is, one recorded on film rather than on canvas. However, Kahlo called herself “the great concealer.” As with her many painted self-portraits, she knew how to present herself. Since her father was a well-known photographer, she understood the power of the camera. As much as these photographs provide us with a rare opportunity to see the actual physiognomy of Kahlo, we are given nothing less than her greatest invention: “Frida Kahlo.”

This was a woman of strong political beliefs, steadfast devotion, a liberated life style, and, due to numerous hardships, a woman who exercised great control. In the photographs here, we are hard pressed to see behind her carefully crafted façade. In her own self-portraits, Kahlo painted herself as both the model, scrutinized by her own gaze, and as the painter, doing the scrutinizing. Here, several accomplished photographers supplant the latter role, and, still, she remains in charge.

Kahlo was photographed by photojournalists on assignment for international magazines and newspapers primarily due to the celebrity of her husband, muralist Diego Rivera. The couple was exceptionally attractive to the photographers for their extreme physical differences, and, in Frida’s case, her unique style inspired by Tehuana indigenous dress. Celebrated photographers such as Gisèle Freund, Lola and Manuel Álvarez Bravo, and Edward Weston made striking portraits of Frida, or Frida and Diego together. The more interesting, accessible images were made by her father, lovers and photographers-turned-friends and revealed an occasional pensiveness or trace of a smile to transform her otherwise uncompromising self-possession.

By revealing little emotion in these, or her own, compositions, Kahlo understood the notion of “transference” (she was familiar with psychoanalysis). We, the viewers, transfer on to her implacable countenance—what Surrealist André Breton described as “a ribbon wrapped around a bomb”—what we see within ourselves. Kahlo evoked a powerful, shared human condition, inclusive of desire, suffering, imagination, and loneliness; she made it palatable, even valiant.

Written by Margaret Hooks, author and Carla Stellweg, art historian and curator.