In my first Coffee with the Curators blog entry in June, I gave an account of my experience in February as an art courier for the Harn’s Champ d’avoine (Oat Field) landscape by Claude Monet. The purpose of this journey was to oversee the installation of the painting in the Claude Monet: Places exhibition at the Museum Barberini in Potsdam, Germany. The show was co-organized by the Denver Art Museum where the exhibition had opened in October 2019 under the title Claude Monet: The Truth of Nature. The much-anticipated return of Champ d’avoine occurred in August. I’m thrilled to see this gorgeous Impressionist gem back in the Harn galleries once again!

Before we could approve Champ d’avoine to be a part of this exciting international exhibition, we needed to be sure that it was in stable condition and safe for travel. Even though we have a carefully constructed custom crate for the painting, travel involves multiple people handling the crate as well as long rides on trucks and airplanes. All of these factors subject a painting to a lot of movement and vibration which can lead to problems if a painting is not in stable condition. For example, there might be slights cracks in the paint or areas where the frame is causing an abrasion on the canvas or painted surface.

We contacted a professional conservator who came to the Harn and examined the painting with her magnifying loupe and under special lighting. Her detailed report indicated that we first needed to address some wear and tear that it has endured over the years, including in its life before it entered the Harn collection. Remember this painting dates to 1890, so it’s now 130 years old!

Museums carefully control the environment (such as temperature and humidity) in their buildings in order to slow the art-aging process. However, even with the best of efforts, time takes its toll on the materials with which art is made, and intervention is sometimes necessary.

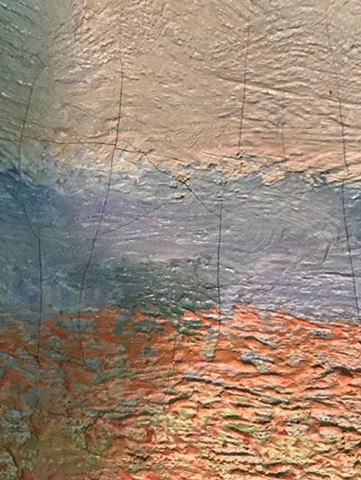

The conservator recommended cleaning the surface of the painting. This involved removing grime with the help of delicate sponges and a solution of distilled water and acetic acid. The conservator’s close examination also revealed that a series of vertical cracks in the paint had begun to lift slightly from the surface of the canvas. These were also visible from the reverse of the canvas. The cracks were stabilized using a bit of adhesive infusion. The goal was to flatten the elevated cracks to prevent the paint from lifting further. The cracks were heated gently to reduce the cupping and tenting (i.e. lifting) from the canvas.

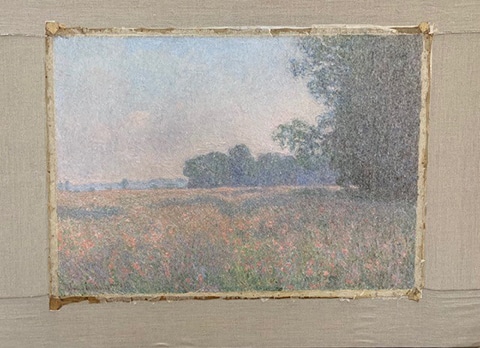

The conservator also removed Monet’s canvas from the wood support, called a stretcher, over which the artist had stretched his canvas before he painted it. In the final picture below, you can see the painting after it was removed from the frame and stretched on a conservator’s loom. The conservator added a thin paper layer directly on the painted surface to protect the paint while working on the cracks in the paint. Part of this process involved gently peeling away areas of the paper in order to expose the areas that needed treatment. The conservator also strengthened weak areas of the edges of the canvas by adding fine linen canvas.

This was not the first time that Champ d’avoine was treated by a conservator. In 2015, the painting was cleaned of surface grime and some minor cracks in the paint were treated. In 2005, a glossy varnish was removed. The varnish had been added at some point before the painting entered the Harn collection. Yet, Monet intended for his paintings to be unvarnished so that the purposeful variation of luminosity and textures in his works could be discerned. Although some art dealers have added varnish to Monet paintings to enhance their brilliance, a number of art museums have decided to remove the glossy, sometimes yellowing, varnish. This is a slow, painstaking process that involves removing the varnish little by little with the aid of organic solvents and cotton swabs. With the careful removal of this added glossy varnish, Monet’s skillfully created atmosphere in Champ d’avoine was no longer obscured.

By addressing the condition of Champ d’avoine periodically, we can ensure that Claude Monet’s landscape will be enjoyed—and seen as the artist intended— for generations to come!