In the North Gallery of the David A. Cofrin Asian Art Wing, the exhibition Tempus Fugit continues to change. A long meditation on time and its qualities, every six months the scene changes to move forward in chronological time. The 51-foot-long handscroll changes positions, the album leaves are turned, we conceptually shift from Autumn to Spring….

The latest change highlights the dramatic change in the arts of Japan with the introduction/flowering of modernism. Around the globe, modernism was defined by broad transformations in Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In Japan, this movement was made even more complex by the speed of influence and rapid societal developments. Western influence had only trickled into the isolationist nation before the major upheaval of the Meiji Restoration (1868); however, rapid industrialization and adoption of Western ideas came crashing in like a flood. (The influence on European art from the influx of Japanese aesthetics is also another example of cross-pollination.)

There is often a tension between the intersection of the traditional and the modern, and that is reflected in the art of modern Japan seen in the galleries:

Haori, Taisho Period (1912–1926), Silk, Gift of Norma Canelas Roth and William D. Roth, 2008.45.5

Details: Robot at the Train Station, A Marine Vessel with Telescope, Biplanes and Stars

While the jacket-length haori seen here is fairly austere and traditional on the outside, the fabric lining the interior shows all sorts of wild modern patterns featuring new modes of transportation or modern ideas (robots!). These images were designed only to be glimpsed in more casual settings among friends or family.

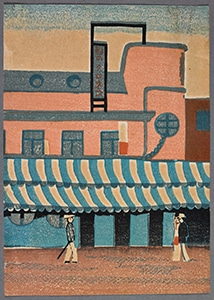

Public buildings were built in a diverse range of Western styles and reflected a new sense of time afforded for leisure opportunities. The subject of the print above is the Musahino movie house, located on the east side of Shinjuku Station. It opened in May 1920, and was quickly established as Tokyo’s premier venue for the presentation of foreign film alongside its Japanese avant-garde films.

Matsuki Manji (Japanese, 1906–1971), Black Cat Restaurant (Fuke no Kuroneko), Showa Era (1926–1989), 1930, woodcut, ink and color on paper, museum purchase, funds provided by the Caroline Julier and James G. Richardson Acquisition Fund, 2017.8.15

The Black Cat Restaurant was also designed in the Art Deco style, with fashionable passersby or patrons seen dressed in 1930s-style Western dress. The older gentleman on the left, indicated by the cane, wears less modern garb.

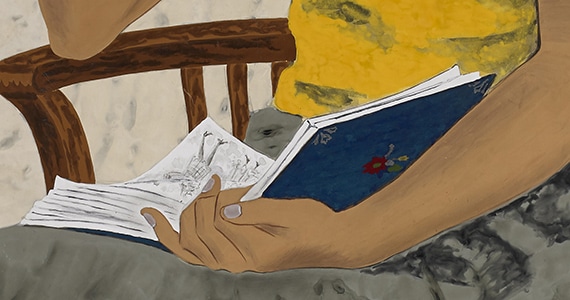

Suzuki Yasuyuki (Japanese, 1911–1980) Daydreaming (Kanjitsu), Showa Era (1926–1989), c. 1938–1940, mineral pigments and sumi ink on paper, museum purchase, funds provided by the Caroline Julier and James G. Richardson Acquisition Funds and the Gladys Harn Harris Art Acquisition Endowment, 2013.59.1

For many, the shift to a modern society included a fervent optimism for the future, and hope for a better world. For women especially, new employment opportunities and shifting roles in a rapidly changing society gave the first glimpse of gender parity.

Japan’s modern girls, or moga, lived independently from their families and were financially self-sufficient. The woman seen in this painting is depicted in stylish Western dress, seated atop a swivel chair and lost in thought while perusing a fashion magazine.

While it was rare for a woman to make a living as an artist in early modern Japan, enrollments into art schools became more and more the norm as time went on—especially after the end of WWII. (And now women students outnumber their male counterparts!) However, there were other important developments in the field. Modern artists not only looked to the West for inspiration through subject matter, but also examined their own working methods and materials.

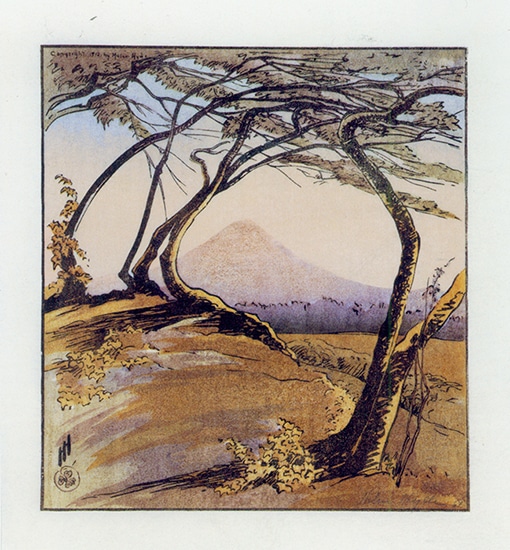

In the Creative New Print style, or sôsaku hanga, artists advocated for a new method in which the artist was the sole creator of everything involved in making the print: the drawing, the carving, the printing. This was a departure from traditional woodblock print tradition of collaborative work between artist, carver, and printer working together.

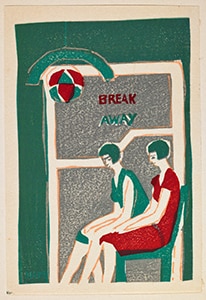

The print seen above is an apt metaphor for this new change: “Break Away” is printed in English across this woodblock print by Nomura Toshihiko. The design of two moga with bobbed-style haircuts in a dance hall was submitted by the artist for the very first volume of the hanga (print) magazine Kitsutsuki, published in 1930.

As you can see, these works illustrate the fluid notion of time and the development of modernism emphasized by the exhibition in both subject matter and method.

See more here: Tempus Fugit.

All Harn photos by Randy Batista. Detail images of haori by author.