All Harn-goers know of El Anatsui’s Old Man’s Cloth, the glittering metal relief sculpture that has hung in our Pavilion and other galleries almost constantly since it was acquired in 2006. The Harn Museum of Art was the first host of GAWU, the exhibition of this body of metal works by Anatsui, in North America, and we’ve followed his rise in the art world ever since. Anatsui is Ghanaian and during recent trips to Ghana, I’ve seen him each time. He comes back to mentor students of his alma mater, KNUST (Kumasi National University of Science and Technology) and take in the burgeoning art scene.

During visits to Ghana to explore new developments in contemporary art in 2016 and 2017, Harn intern Alissa Jordan and former director Rebecca Nagy were awestruck by the array of venues in Accra and Kumasi that they visited. Taking the advice of our colleague Christopher Richards, a UF alumnus, Harn intern, and guest curator, who has done extensive research on Ghanaian art and fashion for his doctorate, we stopped first at the annual exhibition for art students, faculty, and alumni held in the spacious Museum of Science and Technology. Going through three large galleries and the auxiliary buildings on the museum grounds, we were stunned by the installations (pictured below). A reviewer whose article appeared in “African Arts” Journal in 2018 compared this exhibition to those she’d seen in documenta exhibitions in Europe. At least one of the artists, Ibrahim Mahama, who’d wrapped the auxiliary buildings and grounds with cocoa sacking, has presented work in documenta and many other international venues. It seems inevitable that others will be participants in the future.

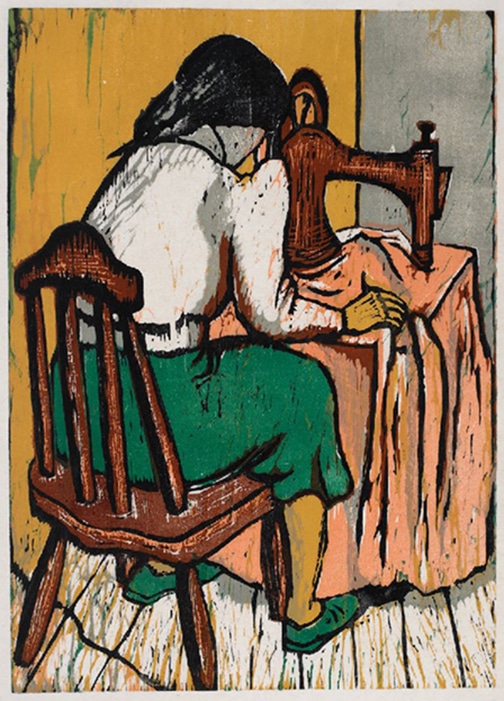

Many of the artists featured in the two KNUST exhibitions as well as others are establishing international reputations. The artist Jeremiah Quarshie, for example, has been active in South Africa, Nigeria, the U.K., and elsewhere in Europe. The Harn acquired his work Obiribea (pictured below) after attending the opening of his exhibition at Gallery 1957 in Accra, seeing his installation at the Kotoko airport, and visiting his studio outside of Accra. Quarshie’s work in the series, Yellow is the Colour of Water, revolves around women and their evolving roles in Ghana, and his portrait of his friend Miriam Obiribea shows her dressed for work as a construction materials analyst, in hardhat and safety vest. Installed in the unfinished shell of a shopping mall under construction that housed his one-man show in Accra, Obiribea was in a perfect setting: amidst the scaffolding and damp smell of fresh concrete, a single light hung above the painting seen far in the distance (pictured below). Viewing the work for the first time there, we had the sensation that this hyperreal depiction was the worker on the job site. That memory lingers every time I see the painting in our galleries.

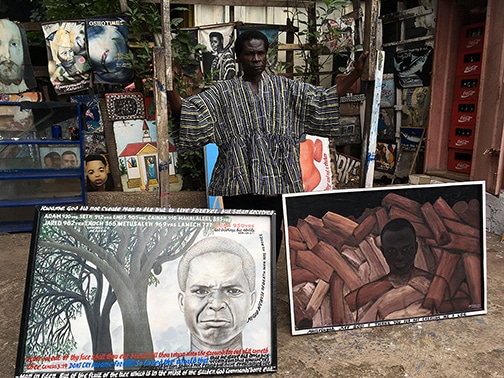

Other works by Ghanaian artists in the collection that have been on view in the last three years include those of George Hughes, Kwame Akoto and Kate Badoe. I was fortunate to visit Akoto’s studio in Kumasi, in 2006, 2016 and 2017, noting that his work has continued to thrive, and has attracted greater international recognition. The Harn acquired two of his works in 2018, and five more were given by the art historian Doran Ross, who has published Akoto’s work and is now planning an exhibition of Akoto’s works at the Fowler Museum at UCLA. An exquisite work now in the Harn’s collection depicting Mami Wata, in her undersea palace, is considered to be one of Akoto’s masterpieces. An inscribed self-portrait of the artist will be on view in an upcoming Harn exhibition that explores the juxtapositions of text and image in art (pictured below). While we can rejoice at the recent blossoming of contemporary art in Ghana and elsewhere in Africa, we can also see promising signs that state and individual patrons continue to support them by growing local infrastructure and networks needed, such as educational institutions, museums, galleries and residences.