This semester, our Harn poet-in-residence Debora Greger and I are having a different kind of internship. Typically, we can be found in the galleries or in storage with undergraduate or graduate student interns, doing object studies on the Harn’s collections or writing new material for in-gallery use. To stay safe in times of COVID-19, Debora and I have our meetings virtually and I suppose we should say having “Tea with the Curator” as we are both tea drinkers.

Toshiko Takaezu (1922-2011), Small Moons, 1980s, glazed stoneware, Gift of the artist in memory of Caroline J. Rister, 2007.17.14, 2007.17.13

Most recently, we have been studying the exhibition Breaking the Frame: Women Artists in the Harn Collections. An extended time spent looking at the mysterious ceramic moons by Toshiko Takaezu (1922–2011) led to an inquiry into the Japanese women writers of the past.

Allysa: Debora, being the great wordsmith that she is, will set the stage for us….

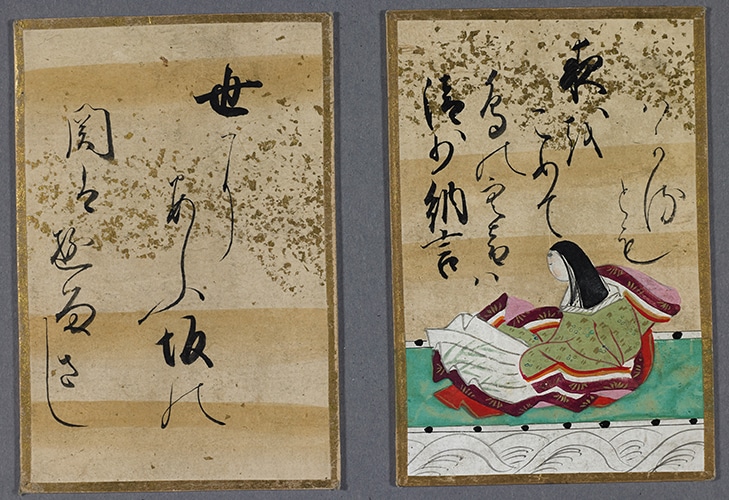

Debora: It is the last decade of the tenth century. In the Japanese court, a woman in her twenties writes miscellaneous notes about her life, whether for herself or to amuse the fifteen-year-old empress. Because women do not use Chinese, the courtly language of official documents and of literature, she writes in Japanese. We don’t even know her real name, just a family name and a title she was given, Minor Counselor. She is Sei Shōnagon.

Her jumble of texts, however it’s arranged, has come to be called The Pillow Book. The great Arthur Waley, first to translate some of it into English, said,

As a writer she is incomparably the best poet of her time, a fact apparent only in her prose. Passages such as that about the stormy lake or the few lines about crossing a moonlit river show a beauty of phrasing that Murasaki, a much more deliberate writer, certainly never surpassed.

For Japanese poets a few centuries later, she was huge. Her prose is where Japanese poetry in the Japanese language begins [Allysa: For a fascinating read about a lesser-known Japanese woman poet, please see Sacred Rites in Moonlight: Ben no Naishi Nikki by UF Professor Emerita, Medieval Japanese Literature, Yumiko Hulvey.]

Things that Arouse a Fond Memory of the Past

Dried hollyhock. Objects used during the Display of Dolls. To find a piece of deep violet or grape-colored material pressed between the pages of a notebook.

It is a rainy day and one is bored. To pass the time, one starts looking through some old papers. And comes across the letters of a man one used to love.

Last year’s paper fan. A night with a clear moon.

In translation, she sounds so contemporary. Today would “looking through old papers” be updated to “scrolling through a smartphone” if she were blogging? Vlogging? Twittering? It doesn’t matter, does it? She’s so timeless it’s hard to keep in mind that in the tenth century a clear moon meant you could see where you were going at night; otherwise, nights were blacker than many of us have ever seen because there’s now so much light pollution from towns and cities.

Unsuitable Things

A woman with ugly hair wearing a robe of white damask.

Hollyhock worn in frizzled hair.

Ugly handwriting on red paper.

Snow on the houses of common people. This is especially regrettable when moonlight shines on it.

A plain wagon on a moonlit night; or a light auburn ox harnessed to such a wagon.

One of the things Shōnagon is treasured for is her way with words. Another is her opinions. She had strong ones regarding things about which it may never have occurred to you to care. Some of hers seem very snobbish today. What would she make of us? (Edith Wharton, a century ago, was appalled that Americans were eating bananas for breakfast.)

Early One Morning

Early one morning, when a pale moon still hung in the sky, we went into the garden, which was thick with mist. Hearing us, Her Majesty got up, and the ladies in attendance joined us in the garden. As we strolled about happily, dawn gradually appeared on the horizon. When eventually I left to go and have a look at the guard-house of the Left Guards, the women ran after me, crying that they wanted to come along. On our way we heard senior courtiers, evidently bound for the Empress’s palace, reciting “So on and so forth—and the voice of autumn speaks.” We hurried back to the palace to converse with the gentlemen on their arrival there. “So you have been out moon-viewing,” said one of them admiringly and composed a poem in praise of the moon.

Shōnagon opened a door for the Japanese poets of the seventeenth century and beyond. They in turn, through translations into French and English, were among the inspirations that led to Modernism in Western poetry. But that is another story.

All photos by Randy Batista.