On a positive note regarding the year 2020, and on the occasion of the Harn Museum of Art’s 30th Anniversary, we are celebrating women artists throughout all of the collecting areas and throughout the galleries. (Please see the exhibition Breaking the Frame: Women Artists in the Harn Collections.) While researching this topic along with the rest of the curatorial team, I had the idea to include one of the most archetypal symbols of feminine power (shakti) to top it off: the goddess. In particular, the most badass version of the goddess, Durga, is now on view in the Asian wing galleries.

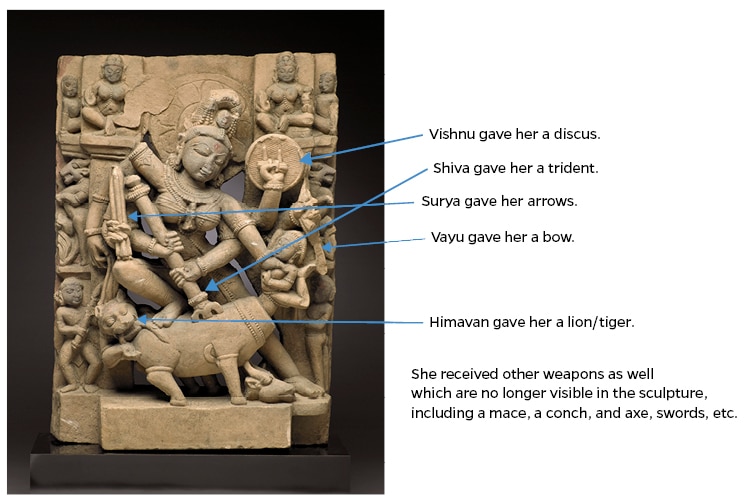

In the Hindu tradition, epics and artistic traditions have represented the struggle between good and evil for centuries—namely, the gods (devas, plural) and demons (asuras). A battle waged by a Buffalo Demon against the gods was not going well as the demon had special immunity from the powers of the male gods. The gods came up with a solution by nominating Durga to defeat him. Durga Mahisasuramardini is the name given to this form of the goddess—it means destroyer of the buffalo demon. This goddess is armed to the teeth, with each of her weapons given to her by a different god.

This 10th-century sandstone sculpture from Central India, where sandstone is abundant, shows the climactic moment after nine days of battle when Durga decapitates the buffalo, and then pulls the demon out in order to dispatch it.

The goddess is multi-armed, an apt representation of her awesome power, and larger in relation to the demon to show her importance. Monumental in size, this sculpture built for a temple niche would originally have had more arms and weapons, but some are now lost.

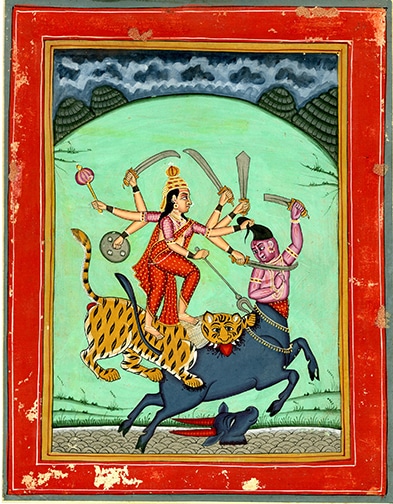

It is fascinating to see the variation in iconography of Durga imagery over time, place, and media. The small copper-alloy sculpture above was made in the late 19th–early 20th century in South India where metal-working is king. In this small 6½-inch-tall votive version, it is also possible to see more of the goddess’s weapons (Note the tiny version of the lion far left!).