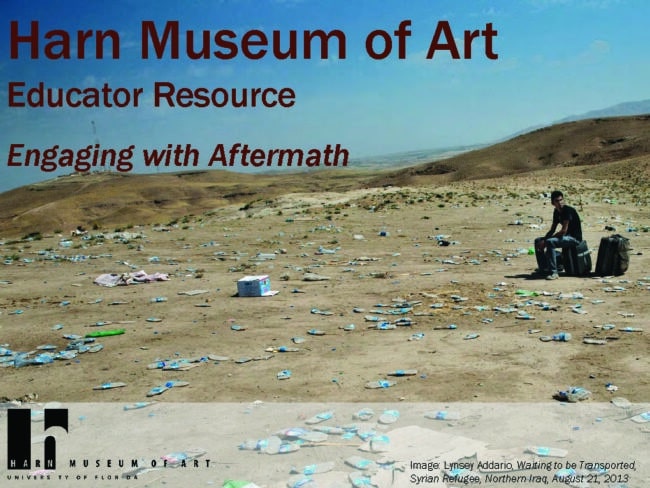

In 2016, I curated a Harn photography exhibition titled Aftermath: The Fallout of War supported by the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts and the National Endowment for the Arts. Aftermath featured several international female photographers in an effort to balance a history of war documented largely by men. The 21st century has spawned more women in the field of conflict photography: Do they see war differently? Their focus was the close periphery of war, the people in harm’s way: children, the wounded and elderly, whole families on the move — women whose survival skills were in overdrive as they negotiated safety, shelter, sorrow, making alliances, preparing food, letting kids play. The work of women.

With the recent news and photographs of the U.S. pulling out of Afghanistan, I thought of the Afghan people in Aftermath, specifically in the photographs by Gloriann Liu. She told me of her many experiences during 25 trips to that country, and how she came to love the people who, she said, changed her life. Gloriann is now unable to travel, not just because of COVID but a life-threatening lung condition. I called her last week to talk about what was happening in Afghanistan. She has many friends there; through them, she learned the complex history of that country, photographed shop owners, families, disabled victims of bombs and rockets, and the dangerous poppy trade (see her images and books here), and personally experienced the distinct brand of Afghan kindness, humor, hospitality, and bravery, all of this influencing how she is now handling her own adversity. I’ve heard similar stories from other photographers about the goodness of Afghans. It makes me hope that when they arrive here, we Americans receive them with the same hospitality they have shown others. Do we ever imagine ourselves in similar conditions? It could happen — it already has for some of us. Hurricanes, fire, floods have turned many Americans into environmental refugees, forced to move to unfamiliar places among strangers to start all over again. Acknowledging our mutual vulnerability, now and in the future, might help us to empathize with the uncertainty and trepidation Afghans will undoubtedly feel once in the U.S.

International author, Teju Cole, has written beautifully about a series of photographs by photographer, Fazal Sheikh (many were made in Afghanistan) in a book titled, Human Archipelago. (Google it, or better yet, buy it.) It is essentially about our current world condition. These are images of difficult places and conditions that will or already have impacted all of us. This is especially true as climate change generates more eco-refugees. We are entering a non-negotiable world in which our openness to each other will mean either our mutual survival or extinction, with the loss of ‘home’ being the first heartbreaking event.

Who then becomes the outsider? Who attends to the ethics of mutual responsibility? Who can put borders around displacement? Who among us will recognize each other as more than the “stranger,” and open ourselves to our mutual interdependence? As Cole says, we are now all “a kind of island chain, interdependent within a single ecosystem.”

Who is the stranger?

Who is kin?

What do we owe each other?

What, in this inferno, is not infernal?– Teju Cole

Afghan shopkeepers who have lost limbs maintain livelihoods despite overwhelming challenges.

A woman’s house has partially collapsed from a snowstorm; rebuilding must start immediately despite her grief.

Young girls wearing traditional student uniforms of white headscarf and black shalwar kameez.