[This essay on Henry Clay Anderson’s photography is short for the sake of this post. Yet it points to the power of photographs to help us see history and make connections. It waits further post-COVID-19 research.]

Henry Clay Anderson lived and worked in Greenville, Mississippi, as the town’s most prominent photographer. He opened Anderson Photo Service in 1948 on Edison Street, downtown (visible in the window beside the motorcycle couple below). In 2002, Separate, but Equal: The Mississippi Photographs of Henry Clay Anderson was published, making Anderson’s photographs more widely known. In 2014, the Harn purchased ten, adding to the museum’s growing, more equitable representation of Americans.

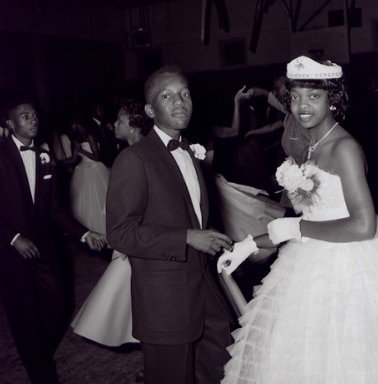

Anderson learned to be a photographer on the GI Bill after serving in WWII. Photographs of his middle-class clients in thriving 1950s Greenville capture beauty, joy and pride. “Poverty and hurt are part of the Mississippi legacy, true enough,” wrote Wil Haygood in The Washington Post, “but Henry Clay Anderson swung his camera, lanternlike, in other directions. …The man’s heart and craft lay in his portraits of folk who stared at a camera with optimism and—damn the uncertainties around them—a ferociousness of pride.”

Such geographies of Black prosperity could be fragile. Anderson’s images bring to mind the once vital town of Rosewood, FL, forty-eight miles from Gainesville where I live. In 1923, Klansman, in Gainesville for a rally, descended on Rosewood, provoked by hearsay. They killed numerous Black citizens and razed the town. What conditions fueled such monstrous acts? How can we work to eradicate them? Rosewood was a post-WWI Jim Crow town, its livelihood dependent on the white-owned lumber industry. After the Great War, racial tensions ran high across the U.S.; Black success was too threatening for some white populations. Yet the power of photographs is that they allow us to see what was, or what others might conceal or destroy. I’ve looked for photographs of Rosewood before that fateful week in 1923, to see evidence of its prosperity, but like the town, they are seemingly gone, or are few and dispersed. Whoever wields power shapes the historical record.

Three decades later, Greenville felt the benefits of the post-WWII economic boom. It was largely mercantile, and for a while, in the 1950s/1960s, prospered during the Civil Rights Movement. It did not experience the terror of Rosewood. Why did Rosewood die but Greenville thrive? What can we learn from the coexistence of Greenville’s black and white citizens during that time?

Anderson’s photographs are beautifully composed and celebratory in feeling: proms, new purchases, beauty pageants, traveling musicians (Delta Blues is integral to Greenville’s identity). His images open up and complicate history by vividly showing us lives lived well. Black Americans know these histories—the rest of us largely do not. Bryan Stevenson’s Equal Justice Initiative reminds us it would significantly thwart racism if we did.

Photos from the Harn Collection:

Henry Clay Anderson (American, 1911-1998)

Motorcycle Riders, Neg: c. 1948; print: 2007

Aunt Hattie Anderson’s Children with a Television, Neg: c.1960; print: 2007

The Prom Couple, Neg: c.1960; print: 2007

Gelatin silver prints

Museum purchase, funds provided by the David Cofrin Acquisition Fund