This blog entry addresses one small facet of the rich interplay between the arts of Japan and the United States in the early 20th century. During this period, many American artists developed an interest in Japonisme—a French term coined by art critic Philippe Burty to describe the fascination with Japanese art and design that swept the United States and Europe. Following the opening of trade with Japan in 1854, vast numbers of Japanese decorative and graphic arts were imported to the West. The colorful and vibrant prints of the ukiyo-e (“pictures of the floating world”) print tradition popularized in the 17th century inspired many American graphic artists to experiment with their own printmaking. Their sources of inspiration included images of Kabuki theater performers, romantic landscapes and scenes from history and everyday life, rendered with clear outlines, precise details and flattened perspectives. Here, I would like to focus on two American artists, Helen Hyde (1868–1919) and Lilian May Miller (1895–1943), who created a distinct body of color woodblock prints inspired by the ukiyo‑e tradition and in collaboration with Japanese carvers and printers. A number of stunning examples of their work are in the Harn’s Modern Collection.

Helen Hyde is recognized as the first American woman artist to study Japanese printing techniques in Japan. She grew up in San Francisco and studied at the San Francisco School of Design and the Art Students League in New York City before continuing her studies in Europe. While in Paris from 1891 to 1894, she became immersed in the European craze for Japanese prints. In 1893, she attended an exhibition of the color etchings of Mary Cassatt (1844–1926), an expatriate American artist living in Paris, whose prints were inspired by Japanese woodblock prints. Cassatt’s images of mother and child may have inspired Hyde to create her own prints focusing on this theme. Hyde’s The Mirror is a tender image of a woman holding a baby whose delight is revealed in the mirrored reflection.

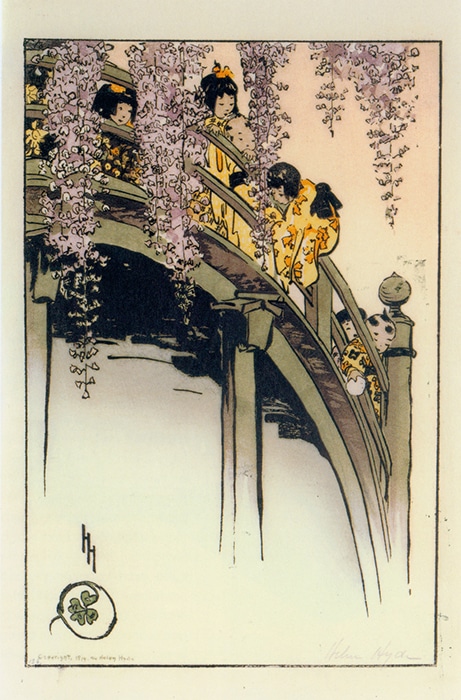

Hyde traveled to Japan in 1899–1901 and returned the following year, remaining mostly in Tokyo until 1914. While in Japan, she learned the fundamentals of color woodblock print production that was traditionally a team effort. Under the artist’s direction, several woodblocks were cut from an artist’s sketch or watercolor painting, each woodblock for a specific color. Then a printer would make prints by pressing the woodblock with its associated colored ink onto paper. Although she studied carving techniques first-hand, she preferred to hire Japanese craftsmen for the laborious tasks of carving and printing woodcuts based on her designs. Yet she supervised or collaborated with artisans, thus exercising creative control over her final product. In the making of Moon Bridge at Kameido and the other prints pictured here, she hired a professional carver named Matsumoto and the printer Murata Shōjirō with whom she produced about forty prints.

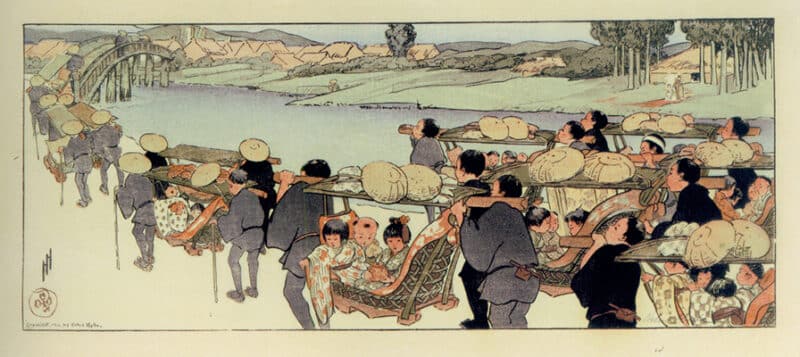

Hyde’s print Going to the Fair is a charming image of young and old traveling along a road against a pastoral landscape vista in the background. This print presents a dreamy image of a bygone era along with a charming narrative subject that appealed to American collectors. Like many of Hyde’s prints, Going to the Fair was printed on delicate tissue-thin paper, an unusual choice for Japanese woodblock prints and one that Hyde’s Western clients perceived as exotic.

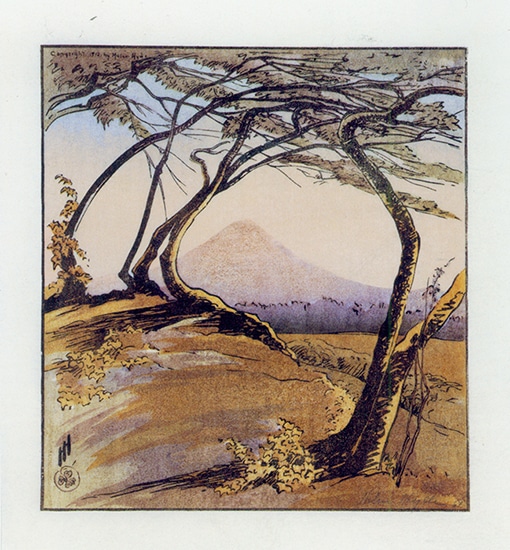

While living in Japan between 1899 and 1914, Hyde returned to the United States on numerous occasions for short stays. Her return visits were usually spent visiting her dealers and overseeing exhibitions of her work. However, she spent most of 1911 in Mexico recuperating from surgery for treatment of cancer. While in Mexico, she remained active creating drawings and watercolors that served as the basis for prints when she returned to Japan in 1912. Mt. Orizaba from Jalapa, Mexico was based on one of Hyde’s sketches made while at the health resort at Jalapa on the east coast of Mexico. The distant mountain is Pico de Orizaba, an inactive volcano that can easily be mistaken for Japan’s Mount Fuji, a recurring image in ukiyo-e prints.

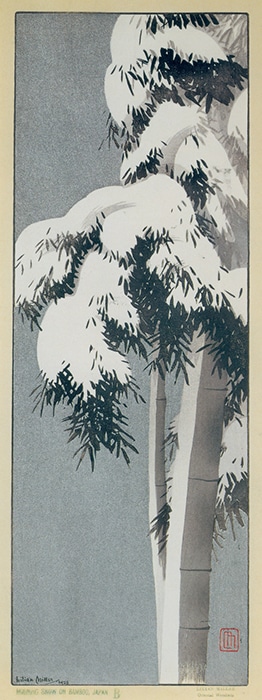

Unlike Helen Hyde who moved to Japan as an adult, Lilian May Miller was born in Tokyo where her father worked at the American embassy. Before her family returned to the States in 1909, she attended classes on traditional painting styles and techniques taught by Japanese artists. Following studies at Vassar College, she returned to Japan in 1919 and soon began making woodblock prints. In contrast to the working method of Helen Hyde, Miller did not rely on Japanese carvers and printers to translate her colorful designs into woodcuts. At first, she collaborated with the professional carver Matsumoto, who had also worked for Hyde, and a printer but eventually learned the techniques of block carving and printing. She carved the woodblock for Morning Snow on Bamboo and may have printed it herself. Her rectangular monogram “LMM” appears on the lower right. Originally printed against a blank background, this version of her simplified bamboo composition was printed with a lush mica ground.

For both Helen Hyde and Lilian May Miller, their print production contributed to financial independence and a middle-class life. Hyde found immediate success selling her prints through dealers in the United States. Her San Francisco dealer purchased the entire edition of her first color woodblock print executed in 1900. Between 1900 and 1913, Hyde had signed her name to an estimated 16,000 prints. Although woodblock printmaking was secondary to Miller’s career as a journalist in Japan and Korea, she continued making prints to supplement her income. Between 1919 and 1922, she had produced more than 6,000 prints and holiday greeting cards that were popular among expatriate Americans who sent them to friends and family back home. Through the successful marketing and sale of their prints to American clients, Hyde and Miller also advanced the popularity of modern Japanese woodblock printing in the United States in the early 20th century.