This year marks the 85th Anniversary of the founding of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) which employed roughly 8.5 million Americans during the Great Depression when as many as 25% of the workforce was unemployed. Established in 1935, the WPA created a series of relief programs, from public works projects—such as the construction of public buildings and roads—to programs for out-of-work artists, writers, musicians and composers. The Federal Art Project (FAP), a branch of the WPA, employed more than 5,000 visual artists who collectively created an estimated 108,000 paintings, 18,000 sculptures, 2,500 public murals and about 200,000 prints. Thousands of women were active in WPA programs like the FAP. With this blog entry, I would like to shine a spotlight on a few of these women and their contributions to WPA-era art.

At its height in 1938, the Graphic Arts Division of the FAP employed around 790 artists in workshops across 36 cities. Many of these artists focused on observing and recording popular culture such as scenes of people at work and at play. Some artists captured important societal issues of the day, especially the effects of unemployment and homelessness. The three artists mentioned below worked in the New York City workshop which was the largest in the Graphic Arts Division of the FAP.

Blanche Grambs (American, 1916–2010) was born in China and moved to New York City in 1934 to study at the Art Students League. During the 1930s, she participated in Communist rallies and activities and was arrested in 1936 at an organized sit-in protesting cuts to the WPA FAP budget. Grambs was driven by her social conscience and her belief that artists could actively combat societal ills. She created powerful images of industrial workers, the poor, and the homeless. In etchings like Cold, where a group of unemployed and homeless men huddle by a fire, she represented the bleakest realities of the Depression-era.

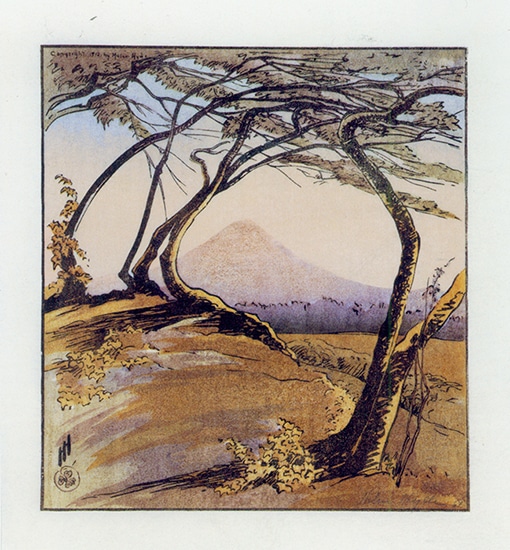

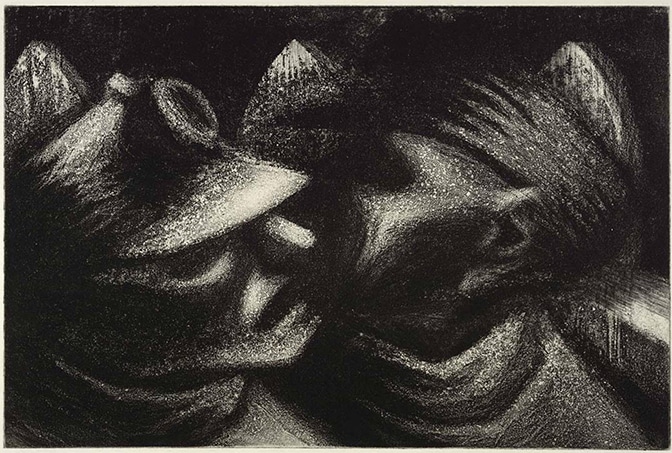

In 1935, Grambs and fellow members of the Art Students League visited a mining community in Lansford, Pennsylvania. This experience inspired her to create her Untitled (Miner’s Heads) aquatint and other images depicting the harshness and misery of the working and living conditions she observed. Following her work with the WPA, Grambs worked as a magazine illustrator and commercial artist and later as an illustrator of children’s books under the name Grambs Miller.

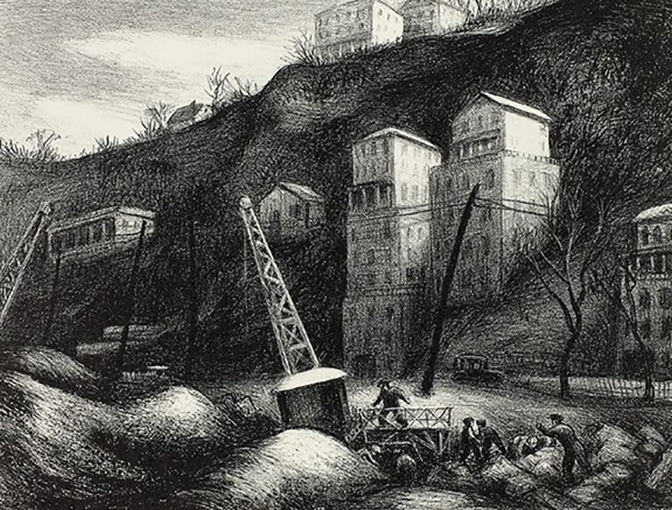

Unlike Blanche Grambs, we know very little about the personal lives and artistic careers of Ann Nooney (American, 1900–1964) and Rosa Rush (American, active 20th century). Yet the prints they created for the FAP provide a glimpse of life in the U.S. during the Great Depression. In Nooney’s lithograph Jersey Relief Project, men are seen working with hoists and digging underground at the base of a large hill with apartments in the background. The setting is a WPA relief project in New Jersey where the WPA spent more than $404 million on construction and infrastructure projects, as well as arts and publications projects.

Work was a common subject in art during the period, yet few artists represented the wage work of women as a central theme. In Seamstress, Rosa Rush depicts a woman who is absorbed with her task. Rather than embodying a cosmopolitan working woman, her seamstress is a solitary figure engaged in a stereotypically female form of employment.

Many of the women who contributed to the graphic arts through WPA programs remain obscure figures today. This is partly because of the fate of WPA prints following the end of the program in 1943 when large numbers of prints produced for the Project were lost, destroyed or reclaimed for materials. Thousands of prints from the New York City workshop were either sent to schools for use as art materials or to Riker’s Island, one of the country’s most notorious correctional facilities, to be used as scrap paper by the inmates.

For more examples of WPA-era art, visit the Harn Museum of Art’s modern art gallery where a selection of prints is on display through February 2021.