After a month of being homebound due to the pandemic, I reached out to the artist Didier Viodé, curious about his response to this global phenomenon. Years ago Viodé emigrated from the Republic of Benin to France where he has established his career as a sequential artist, video artist and painter. Much of his work is devoted to current events, including the surge of immigrants from Africa and elsewhere into Europe as seen in his series of ink drawings Les Migrants. The Harn acquired four works from the series in 2018, three showing advancing crowds of people rendered as an amorphous wash (Fig. 1), and one a closer view of adults and children pressed against a barbed-wire barrier. In one image, figures of adults and children with agonized and monstrous mask-like faces, seem to howl in unison (Fig. 2). Their distorted and frightening features recall two masks on view in the current Harn exhibition Elusive Spirits: African Masquerades, an Ibibio Mbop mask and an Igbo Okoroshi ojo mask that both embody spirit beings, who are temporarily on earth to communicate with humans. They are transient, supra-human forces to reckon with.

I perceive the blurred and ambiguous figures in Viodé’s paintings as conjuring the despair and dehumanization of people caught in the global convulsion that has displaced millions of people. Rendered as ephemeral ink-wash figures, fading in and out of focus and floating on a white background, is metaphoric of their temporal and spatial transience and conveys a precarious sense of place. Yet he also depicts exiles bonded to one another as a unified group, capable of unfathomable strength, compassion, and drive for a new life, as in one image of someone lifting another person on his shoulders while others run behind them (Fig. 3).

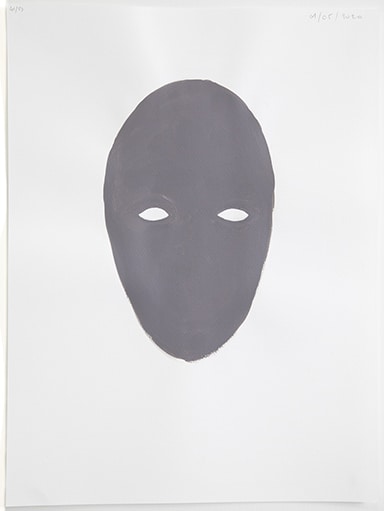

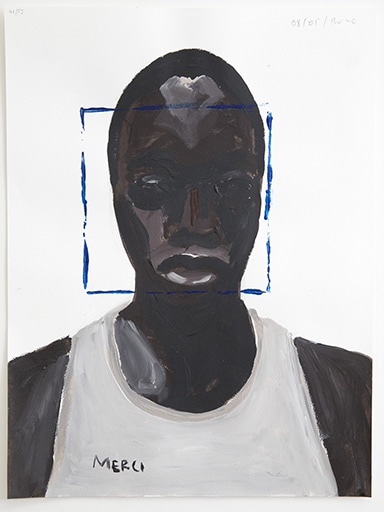

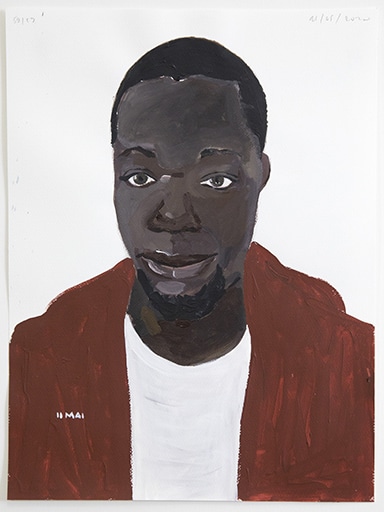

Some of these themes resurface in his current work, done in his home in isolation, a series he calls confiné (confined). Viodé resolved to do a series of self-portraits, one each day, to document his own state of mind during the lockdown. The result is 59 acrylic paintings that show a fantastic transformation. Starting with solid and conventional painterly headshots (Fig. 4), he shifts after several days to more abstracted versions and disjointed body shots. Gradually his body dissolves and wavers in the pictorial space. His features are reduced to a stain on the paper. In the middle of the series, the face disappears entirely as we see a flat white ground with a floating blue facemask, the kind we’re all too familiar with. This mask metamorphoses into an ovoid face mask (Fig. 5), which the artist identifies as an African mask, and, for me, recalls the reductive and elegant masks by Dan artists of Côte d’Ivoire and Liberia. After total transformation, Viodé slowly brings himself back into focus (Fig. 6), first with a few contours, then through bolder brushstrokes. Has he changed in the process? I perceived a faint smile on his lips in his last image, perhaps a sign of relief, hope, or amusement (Fig. 7).

I mused about Viodé’s series and its implications in this historically unprecedented moment when all of us are transformed by a common threat, and all of us are behind many layers of barriers, separating and concealing us. How will our connections with ourselves and our world change us? As our identity shifts, personally and collectively, what will stay the same? And one last query about the mask images: are Viodé’s masks a reminder of our common human heritage in Africa and, thus our collective Africanity?