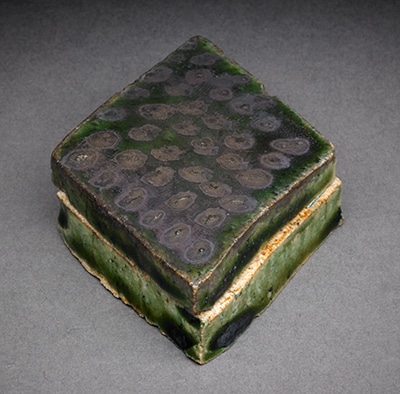

During the month of May we celebrate the heritage of Asian Pacific American communities and their contributions to pluralistic American history, society, and culture. The Harn Museum of Art’s collection encompasses works of art by Asian American artists such as Japanese-American sculptor Isamu Noguchi (1904–1988), ceramicist Toshiko Takaezu (1922–2011), and Korean-American new media artist Nam June Paik (1932–2006). Their dual heritage and cross-cultural perspectives not only shaped their artistic expressions as shown in Isamu Noguchi’s ceramic art but also continuously inspire artists around the world.

Born in Los Angeles in 1904 to American mother Léonie Gilmour, a literary lover, and Japanese father, Yonejiro Noguchi, a noted poet, Isamu Noguchi lived in Japan until the age of 13 when he moved back to the United States. Complicating his biracial and bicultural upbringing was his father’s abandonment when he was a child. In search of his identity straddling two cultures and his voice as an artist with a combined legacy, Noguchi kept reinventing himself and created artworks that cross cultures and boundaries.