I’ve been listening to a BBC podcast titled Great Lives, where a famous living person nominates an oftentimes lesser-known deceased person. The celebrity, and an ‘expert’ (usually a biographer of the dead nominee), discuss the career of the chosen ‘Great Life.’ The program makes me feel hopeful that such people once existed in the world and worked (mostly) for the betterment of the human race. If I were asked to nominate a great life, it would be artist, activist and art therapist, Cliff Joseph.

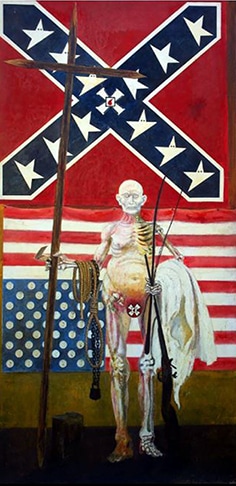

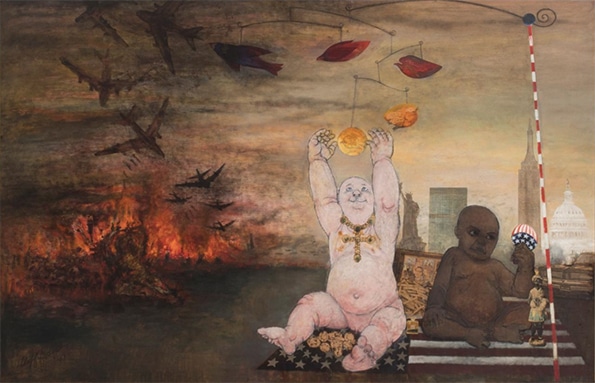

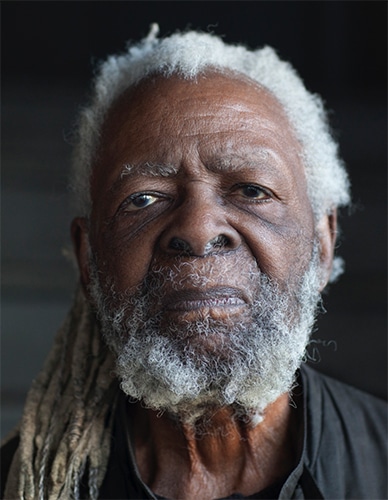

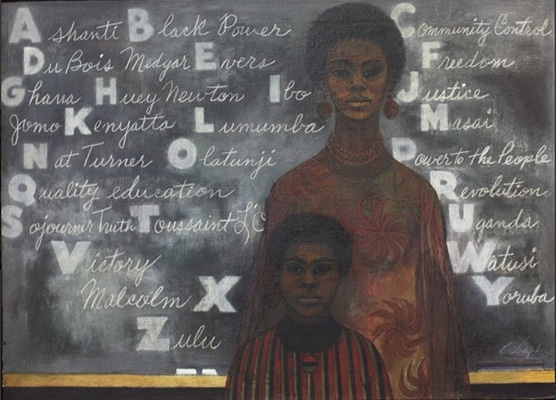

Mr. Joseph’s was indeed an impressive life: creative, purposeful, generous and wise. He lived 98 years and died November 8, 2020, of natural causes. His portrait (seen here) was used for his New York Times obituary and is currently on view at the Harn Museum in Terry Evans: Stories of the American Prairies. Through Evans, I was introduced to Cliff Joseph and chose his portrait for our Harn exhibition after Evans explained his environmental activism and his powerful art. Terry worked with Joseph against industrial pollution that was allowed to fester and grow near poor neighborhoods. The Harn subsequently purchased one of Joseph’s artworks, Blackboard, that will be exhibited in a future show titled, Text + Image. I called him on the phone to thank him. When hanging up, he said, “Give Florida my love.” His kindness is combined with a critique of our nation’s deep-seated prejudice seen in his no-holds-barred imagery that incriminates discrimination.

Born in Harlem and inspired by Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., Joseph applied his energy and talent toward visual expression, alongside demonstrating against racism especially in the art world. His aim: to wake up the blind complacency of white power systems. In 1969, he demonstrated with colleagues against the Metropolitan Museum’s exhibition, Harlem on My Mind — a show about Harlem with all-white artists! He helped found the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition, which loudly protested against, and campaigned for African-American inclusion in museums. In 1971, the Whitney Museum mounted the exhibition, Contemporary Black Artists in America, curated by a white curator. Joseph declared such curation should, “be selected by one whose wisdom, strength and depth of sensitivity regarding Black art is drawn from the well of his/her own Black experience.” On opening day, sculptor Richard Hunt, painter Sam Gilliam, and a dozen other Black artists withdrew from the show. Joseph was among the pioneers who made “multiculturalism” a part of our vocabulary. After the 1971 Attica Prison Uprising, art therapist Joseph insisted on bringing racial sensitivity and cultural awareness to the profession. He wrote to New York’s mayors and governors over the years who eventually supported artmaking as part of the state’s prison and mental health educational systems. “Those who are at the head of the oppressive system know well the power of art, and fear it in the hands of the people,” Joseph wrote. “That is why power structures throughout man’s history have sought to suppress and control the creative artist.” When looking back on contributions to cultural awareness, Joseph said, “It’s not that a person has to be Black to deal with Black patients (or prisoners). But if a white person comes in to deal with a group of Black people, that person should know that a culture-specific approach should be used.” A full interview with Cliff Joseph can be seen in this 2006 documentary. May Cliff Joseph rest in peace knowing he made the world a better place for all. A Great Life, indeed.