The Harn is curating an exhibition that will open this July running through next January titled Shadow to Substance (more on this in a moment). Let me explain the enigmatic title. In the early history of photography, from 1839 to about 1870, the science of photography was sometimes referred to as “fixing a shadow,” because, before photography, a popular portrait method was to draw a silhouette of a person, a kind of shadow (below left) that was then mounted on ivory (usually) and framed as a keepsake of the sitter. Photography’s invention sought to fix that shadow, or silhouette, but added, of course, far more detail and realism, describing freckles on a face, the sweep of a hairstyle, the precision of a necktie. In a matter of a few decades, portraits (other than paintings, that is) went from paper cutout profiles to information-laden fixed “shadows.”

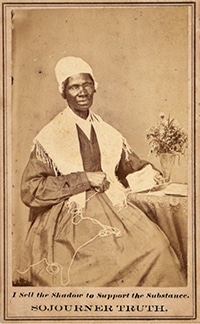

Enter Sojourner Truth, a peripatetic firebrand at the peak of her career just as photography and the Abolitionist Movement were gaining momentum in the U.S.

Born Isabella Bomfree (1797–1883) in Dutch-speaking upstate New York (English was her second language, it should be noted), Truth was an enslaved woman until 1827. After securing her freedom, God gave her the name “Sojourner,” she said, since she traveled far and wide with her message (although never down South, also to be noted); and God gave her a second name, “Truth,” for the truth of what she had to say. Fighting for the freedom of enslaved people became her life’s work. She preached abolitionism, equal justice, Christian redemption, temperance, and women’s rights. She is most noted for her women’s liberation speech, Ain’t I a Woman?, delivered at the 1851 Women’s Convention in Akron, Ohio. White newspaper reporters at the time recounted that she delivered it in her own southern negro dialect, and wrote it up thus (scholars think this was done for less than noble reasons, although we still see it written and reenacted this way), when, in fact, Truth never visited the South, and spoke English with a Dutch accent. Although she could not read or write, Truth had a charismatic presence and was a powerful public speaker. Her friend, Frederick Douglass, said her campaigning style was a “compound of wit and wisdom, of wild enthusiasm, and flint-like common sense.”

Sojourner Truth was among the most photographed women of her generation. She embraced the power of the medium in order to inform people, selling her photographic portrait (and her books) at her lectures in the carte-de-visite format (the size of a calling card) for 25 cents. This supported her work. Printed on the margin of her photo was: “I sell the Shadow to Support the Substance.” The sale of her shadow, she reminded listeners, gave substance to not only the specificity of her own life and physiognomy but to other Black lives. She hoped her life and theirs would, in the imaginations of her largely white audiences, become vivid, individual, and complex.

It could be said hers were the first celebrity photographs in America (although photographs of Abraham Lincoln were likely the ‘first,’ his visage being the most collected then and now). Yet, by selling her portrait, Truth’s image could be the first “GoFundMe” project — people bought her shadow to subsidize her cause.

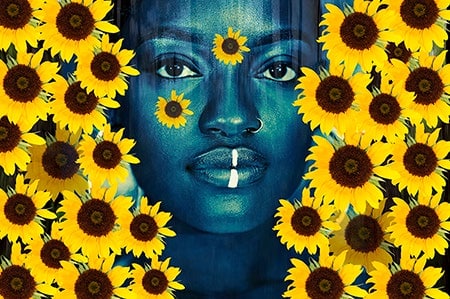

The Harn’s Shadow to Substance exhibition – curated by Kimberly Williams (UF Ph.D. student, English), Porchia Moore (Assistant Professor, UF Museum Studies) and myself — will give visual substance to Black lives now, through new photographic comparisons, variants on beauty and thought-provoking scholarship. It begins with historical black-and-white photographs of Jim Crow Florida and the 1960s Civil Rights Movement from the Smathers Library and Harn collections. The exhibition then transitions from these small, historical images to large color photographs depicting current events: Ieshia Evans’s 2016 protest, Tricia Hersey’s Nap Ministry, Farming While Black land reclamation, a symbolic portrait of Trayvon Martin, British Rapper Ty’s Work of Heart, and more. We are in the process of acquiring new photographs by contemporary Black artists, giving substance to shadows past and present. Dynamic lectures, a soundtrack and an interactive reading list will be available to experience in person (we hope). Stay tuned.